Questioning Offit. Part 13. MMR and autism

Previous parts:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: DTP

Part 3: Encephalopathy

Part 4: Dravet syndrome

Part 5. SIDS

Part 6. West syndrome

Part 7. Hib

Part 8. Hepatitis B

Part 9. Pneumococcus and rotavirus

Part 10. HPV

Part 11. Lawsuits

Part 12. Wakefield

All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed.

Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Chapter 6 (continued)

After praising the scientific community for ostracizing Wakefield, Paul Offit refers to a number of studies that, in his view, prove there is no link between vaccination and autism. These are some of the most frequently cited studies on the topic of vaccination. They fall into two categories. The first group of studies argues that the MMR vaccine (against measles, mumps and rubella) is not associated with autism, while the second group concludes that the mercury-based preservative thimerosal is not linked to autism. All of these studies are epidemiological. As we have noted earlier, epidemiological or ecological studies, by their very nature, cannot reliably establish causal relationships. Nevertheless, let us examine them in more detail. This section focuses on the studies exploring the link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Offit:

Further, no one identified brain-damaging proteins in the bloodstream of children who had received MMR. Finally, twelve separate groups of researchers working in several different countries examined hundreds of thousands of children who had or hadn’t received MMR. The risk of autism was the same in both groups.

The first footnote cited by Offit has nothing to do with “brain-damaging proteins.” It is merely a paper about certain genes being associated with autism. The second footnote includes 14 studies, which we will examine in more detail.

First of all, it should be noted that none of these studies compared vaccinated children with completely unvaccinated ones. In every case, the comparisons were either between children who received the MMR vaccine and those who received other vaccines, or they were correlational studies examining MMR coverage and autism rates. At the same time, the number and composition of vaccines given to the control group were not accounted for, and it is entirely possible that they received even more vaccines than the MMR group.

Nevertheless, even with such a design, the authors of each of these studies had to resort to various methodological maneuvers in an attempt to demonstrate the absence of a link between MMR and autism—and in many cases, they did not fully succeed.

1. Taylor, 1999

This British study concluded that autism rates did not rise sharply after the introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1988, but rather increased gradually over time.

On this basis, the authors draw the following conclusion: since there was no sudden spike in autism rates immediately after the start of mass vaccination, the MMR vaccine cannot be linked to autism.

However, the study overlooks the fact that older children received the MMR vaccine as part of a “catch-up vaccination campaign.” Thus, the authors mistakenly conclude that, because autism was also diagnosed in children born before 1988, the vaccine cannot be the cause.

Moreover, the authors did in fact observe clustering of autism diagnoses within six months after vaccination. Instead of considering this as a potential indication of a link between vaccination and autism, the authors concluded that when parents can’t remember the exact age when symptoms began, they simply guess by saying 18 months. Based on this assumption, all cases with symptom onset reported at 18 months were excluded from the analysis. After this exclusion, the reanalysis no longer showed a statistically significant association.

In other words, despite its flaws, this study found a statistically significant association between vaccination and autism—but the authors dismissed it and concluded there was no link. Since very few people read full-text articles, this study, which actually showed a correlation between vaccination and autism, is widely cited as evidence that there is no such link.

This was a case-control study conducted in Atlanta. The authors found that by age three, children with autism were 1.5 times more likely to have received the MMR vaccine compared to children in the control group. In the 3–5-year age group, the association was even stronger: vaccinated children were 2.5 times more prevalent than in the control group.

However, the authors explained this by suggesting that children with autism may have been vaccinated at an earlier age in order to enroll in early intervention programs for autism treatment—programs that allegedly required vaccination as a prerequisite.

In other words, our familiar figure Frank DeStefano from the CDC found a statistically significant association between vaccination and autism, even noting it explicitly in the abstract—but then dismissed it with a speculative explanation. Just like the previous study, this paper is frequently cited as evidence that there is no link between MMR and autism, despite the fact that such a link was actually found. This is possible because even abstracts are rarely read in full. We will return to this study later.

3. Madsen, 2002

This Danish study reported that the risk of autism among children who received the MMR vaccine was 17% lower than among those who were unvaccinated. In other words, according to the authors, the vaccine supposedly had a protective effect against autism.

The study was criticized in the same journal in which it was published. Professor of epidemiology Walter Spitzer pointed out that if we assume only 10% of children are at risk for regressive autism, then with the study’s design, the data would actually show a fourfold increase in risk associated with MMR. But when all forms of autism are lumped together into one diagnosis, this association is diluted, creating even the appearance of a protective effect.

Another researcher noted that the study analyzed not actual autism cases, but person-years—a standard method in epidemiological research, but ill-suited to chronic conditions like autism. This approach distorts results, because cases diagnosed at an early age (a minority) are given disproportionately high weight compared to those diagnosed later. Moreover, in this study, unvaccinated children were followed for an average of 5 years, while vaccinated children were followed for only 3.7 years. This significantly reduced the chances of detecting a diagnosis in the vaccinated group. At the time, the average age of autism diagnosis in Denmark was about 5 years—meaning a substantial number of vaccinated children simply hadn’t reached the age of diagnosis within the study period.

Incidentally, Poul Thorsen, one of the authors of this and other Danish studies, and director of the Danish Center for Autism Research, was charged in 2011 with embezzling over a million dollars from the CDC. Since then, he has remained in Denmark awaiting extradition to the U.S., but for some reason, in the 14 years that have passed, he has still not been arrested—despite the fact that he hasn’t gone into hiding and continues to work and publish scientific articles.

This was a small study—only 96 children—with a rather convoluted and questionable design. The authors formulated six assumptions supposedly derived from Wakefield’s concept of a "new variant of autism" (the so-called autistic enterocolitis), and then proceeded to disprove them one by one. For example, they assumed that symptoms in children with regressive autism should differ from those in children with non-regressive autism. Or that childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD) should occur more frequently after MMR vaccination—but since their sample included only one such case, they concluded this disproved the hypothesis.

However, Wakefield never actually proposed a new subtype of autism. What he did was suggest a possible link between autism and gastrointestinal inflammation, and he hypothesized that the MMR vaccine might play a role in this process. He never claimed the existence of a distinct form of autism.

The Cochrane systematic review, in its attempt to analyze this study, concluded that “The number and possible impact of biases in this study is so high that interpretation of the results is impossible.” Nevertheless, this has not prevented the study from being widely cited and presented as one of the key pieces of research supposedly refuting Wakefield’s findings and proving there is no link between vaccination and autism.

It’s also worth noting that the study’s author, prominent child psychiatrist Eric Fombonne, has consistently denied the existence of an autism epidemic. In his 2001 paper, he claimed that there was no real increase in autism rates, just a change in diagnostic criteria. He has maintained this position to this day—despite the fact that between 2001 and 2025, autism prevalence in the U.S. increased sixteenfold, from 1 in 500 to 1 in 31.

5. Honda, 2005

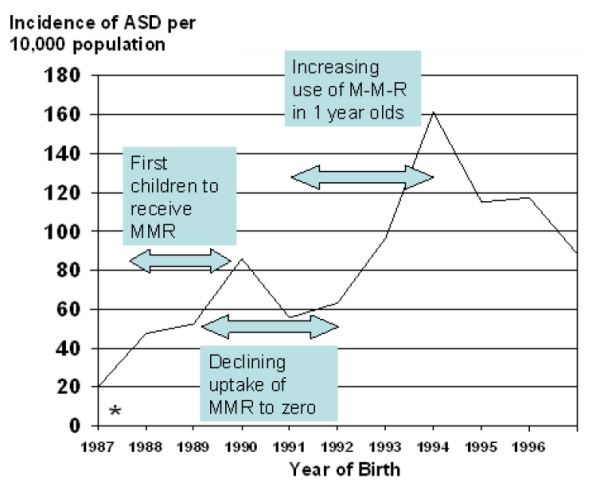

In Japan, the MMR vaccine was discontinued in 1992 due to a high incidence of aseptic meningitis caused by the mumps component, and was replaced in 1994 by separate measles and rubella vaccines. MMR coverage dropped from 70% in 1988 to zero by 1992. This created a natural experiment in which, for a period of time, children were not vaccinated against measles at all. The authors concluded that they found no correlation between MMR coverage and autism rates.

First, the authors fail to mention that the prevalence of autism in Japan increased fourfold following the introduction of the MMR vaccine.

Second, in the charts included in the study itself, it is clearly visible that as MMR coverage began to decline, autism rates also started to fall, and then began to rise again once the monovalent measles and rubella vaccines were introduced. In fact, this study more likely supports a connection between vaccination and autism than disproves it.

Incidentally, one of the authors of this study was Michael Rutter, often called the "father of child psychiatry," whom we already met in the previous part. Unsurprisingly, he did not disclose in this study that he had a conflict of interest—namely, that he testifies in court on behalf of pharmaceutical companies, arguing that vaccines are not linked to autism. That, however, didn’t stop him from testifying in the GMC trial against Wakefield, claiming that Wakefield should lose his medical license for failing to disclose in his own paper that he was serving as an expert witness on behalf of families claiming vaccine injury.

***

The next four studies have no control group whatsoever. They attempt to analyze the connection between vaccination and autism by comparing vaccinated children to themselves.

6. Mäkela, 2002

This article is often referred to as “the Finnish MMR study.” The authors reviewed how many children were hospitalized with an autism diagnosis between 1982 and 1986. They found no clustering of cases related to MMR vaccination and concluded there was no link between the vaccine and autism.

However, the Institute of Medicine noted in its report that the main problem with this study is that it only examined hospitalizations—whereas the vast majority of autism cases do not require hospitalization.

7. Kaye, 2001

The authors of this British study analyzed 114 cases of autism between 1988 and 1993. They claimed that MMR vaccine coverage remained stable at around 95% during that period, while autism prevalence increased. From this, they concluded that MMR is not associated with autism.

This study has been criticized by a number of researchers. They pointed out that autism diagnosis criteria may have changed during those years; that the age of first MMR vaccination dropped from 15 months to 12 months; that 114 cases is a small number on which to base strong conclusions; that the assumption of constant 95% vaccine coverage may not be accurate; and that this type of study design is, in principle, incapable of ruling out a causal relationship.

The authors also failed to take into account that in 1992, the Hib vaccine was added to the UK immunization schedule.

8. Dales, 2001

This study, similar to the previous one, was conducted in California. The authors created a graph showing MMR coverage from 1980 to 1994 and another showing autism prevalence during the same period. They compared the two visually and concluded that since vaccine coverage remained fairly constant while autism prevalence rose sharply, MMR vaccination could not be the cause.

This study was also criticized by other researchers, who wrote in the same journal that the vaccination coverage graph was too compressed, making any correlation hard to see. But when a proper statistical analysis is applied, a relatively high correlation between MMR coverage and autism prevalence actually emerges. In addition, during the study period, the recommended age for MMR vaccination dropped from 24 to 17 months.

Moreover, the authors again failed to account for the fact that during these years, the Hib vaccine and the hepatitis B vaccine were introduced into California’s routine immunization schedule.

This is a self-controlled study analyzing the same data used in Taylor, 1999 (see study #1). As a reminder, that study detected a temporal clustering of autism diagnoses shortly after MMR vaccination—but dismissed it based on the claim that parents were simply misremembering the onset of symptoms.

Interestingly, this study was authored by Professor Paddy Farrington, a statistician and the creator of the self-controlled case series method, which is widely used to demonstrate vaccine safety. While his method is legitimate in principle, it assumes that adverse vaccine reactions follow a Poisson distribution. This may be appropriate for short-term events like febrile seizures, but it is not well-suited to long-term outcomes like autism.

The remaining five articles are not original research studies but rather reviews and opinion pieces discussing previously mentioned studies: DeStefano, 1999, Fombonne, 1999, Halsey, 2000, Offit, 2003, Wilson, 2003

So, out of the 14 sources cited by Offit, only three studies actually compared MMR-vaccinated children to those who did not receive the MMR vaccine (though many in the control groups were vaccinated with other vaccines, including monovalent measles, mumps, or rubella vaccines).

Some of these studies did find statistically significant associations between MMR and autism—but the authors simply dismissed these findings because they didn’t align with the expected conclusion.

In addition to these, two more similar studies were published after Offit’s book: Jain, 2015 and Hviid, 2019. Both are analyzed in detail here.

***

Now let us return to the study led by our familiar figure, Frank DeStefano, who headed the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office. One of the study’s co-authors was William Thompson, who later admitted that he and his colleagues had discovered a significantly increased risk of autism among African American boys who received the MMR vaccine before the age of 36 months. However, according to Thompson, this data was deliberately omitted from the final publication, and the original data files were destroyed.

Defying his superiors, Thompson kept copies of the data. He shared this information with Brian Hooker—a biostatistician whose own son developed autism after vaccination—through a series of phone calls, which Hooker recorded. Thompson instructed Hooker on how to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to obtain the CDC’s original dataset. Hooker received the data, conducted his own analysis, and found that MMR vaccination before the age of two was associated with a 340% increased risk of autism among African American boys, compared to those vaccinated later.

Hooker published his findings in a peer-reviewed scientific paper, which was accepted and published—but retracted within hours of the story airing on CNN, on the grounds of an “undeclared conflict of interest.” Meanwhile, the original CDC paper—whose authors had allegedly withheld part of the data—was never retracted and is still cited today as “evidence” that there is no link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Let that sink in: CDC scientist William Thompson accused his colleagues—including Frank DeStefano, the head of the CDC’s Vaccine Safety Office—of destroying data that suggested the MMR vaccine may be unsafe. He provided evidence to support his claim. And yet, this story was met with silence—from journalists, from FBI, from scientific organizations, and from Congress.

***

Offit summarizes these studies as follows: "For scientists, these studies ended the concern that MMR caused autism."

However, a Cochrane systematic review that examined these same studies found none with a low risk of bias. In fact, it concluded:

“The design and reporting of safety outcomes in MMR vaccine studies are largely inadequate.”

Still, Offit is right in one sense: these low-quality studies did effectively shut down the discussion. In the past 20 years, the topic has been barely studied at all.

***

Later in the chapter, Offit provides a detailed account of the Omnibus Autism Proceeding—a consolidated legal case that combined around 5,000 lawsuits filed by parents who claimed that vaccines had caused autism in their children.

He writes:

If successful, the action threatened the viability of a program that had once saved vaccines. It was a seminal, defining moment... If the special masters decided in favor of the five thousand children, the cost could be as high as $4.5 billion, wiping out reserve funds.

Naturally, such a lawsuit could not be upheld—something Offit notes with evident relief.

What he does not mention, however, is that after the case concluded, the U.S. government began secretly settling individual claims. One such case was that of Hannah Poling, whose family received a compensation of $20 million.

At the age of eighteen months, Hannah received nine vaccines in a single day, after which she rapidly developed regressive autism. Her father, neurologist Jon Poling, carefully documented all of her medical records and diagnostic evaluations. He collaborated with Dr. Andrew Zimmerman, one of the leading pediatric neurologists in the U.S. and a regular expert witness in vaccine court, where Zimmerman had consistently testified that the MMR vaccine did not cause autism.

However, in Hannah Poling’s case, Zimmerman issued an opinion acknowledging a link between the vaccination and her autism. Initially, Hannah had been one of the plaintiffs in the Оmnibus case, but her case was separated out into a closed, individual proceeding and sealed from public view.

The fact that Zimmerman had changed his position only came to light later, due to a leak from a lawyer to a journalist. After this case, Zimmerman was no longer invited to testify as an expert in vaccine court. Nonetheless, his earlier testimonies—given before he changed his view—continued to be used as evidence to reject the consolidated lawsuit.

Hannah Poling’s case is far from isolated. Phil and Misty Hiatt, parents of triplets harmed by vaccines, received $5.1 million in compensation for their daughter’s autism. The family of Bailey Banks was awarded over $800,000 after he developed acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following the MMR vaccine, which later progressed to a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD).

A 2011 study analyzed around 1,300 cases adjudicated through the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program and found that in at least 83 of them, compensation had been awarded to children diagnosed with autism—even though the official position remains that there is no link between vaccination and autism, and the omnibus lawsuit was dismissed. Since most such cases are sealed, the researchers formed a special task force that contacted families involved in the claims process directly.

In her investigative reporting, Sharyl Attkisson found that claims citing “encephalopathy” were typically approved and compensated, whereas cases with the same symptoms diagnosed as “autism” were generally rejected. Attkisson identified approximately 1,300 court-awarded cases of brain injury attributed to vaccination.

***

Let’s return to the research. Once again, it’s important to emphasize that all the studies cited by Offit—and those typically used as “evidence” that vaccines don’t cause autism—focus on only one of the sixteen vaccines (MMR), and one of the many vaccine components (thimerosal). Therefore, even if these studies were flawless, all they could prove is that the MMR vaccine does not cause autism, and that thimerosal does not cause autism.

As we discussed earlier, existing studies are insufficient to conclude that the MMR vaccine is not linked to autism. We’ll examine the research on thimerosal in the next part, but for now, let’s consider another category of studies—those comparing vaccinated children with completely unvaccinated.

These studies are not difficult to conduct using existing data, yet the CDC has been reluctant to carry them out, despite the fact that the Institute of Medicine, in its 2013 report, recommended that the CDC do so. Nevertheless, a few such studies exist—though the CDC had no involvement in any of them.

In 2017, a pilot study was published showing that vaccinated children were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism than completely unvaccinated children. This study had significant limitations: it was retrospective, based on anonymous surveys, and included only 405 vaccinated and 261 unvaccinated homeschooled children.

A 2020 study analyzed data from 2,000 children in three pediatric clinics. It found that vaccination before 12 months of age was associated with a twofold increased risk of developmental delays and a fourfold increase in asthma risk. The later the children received vaccines, the lower their risk of developmental disorders.

A similar study was published in 2021. The authors analyzed data from more than 800 children across three medical practices. They concluded that fully vaccinated children were diagnosed with severe allergies four times more often, autism five times more often, gastrointestinal disorders fourteen times more often, asthma eighteen times more often, ADHD twenty-one times more often, and chronic ear infections twenty-eight times more often than completely unvaccinated children.

Lack of breastfeeding and cesarean delivery were additional risk factors for the aforementioned conditions. For example, among vaccinated formula-fed children, autism occurred twelve times more frequently than among unvaccinated, breastfed children. Vaccinated children born via cesarean were nineteen times more likely to develop autism compared to unvaccinated children born vaginally.

In 2025, the largest such study to date was published. It included 47,000 children in Florida enrolled in the Medicaid program. Its design was significantly more robust than previous studies, encompassing all children under 9 years old registered in the system.

The study found that vaccinated children had a 2.7 times higher risk of autism compared to unvaccinated children. The risk of hyperkinetic syndrome was 2.8 times higher. The risk of epilepsy or seizures—3.5 times higher. Learning disorders—7 times higher. Encephalopathy—5 times higher. Tic disorders—6 times higher.

The study also found that the more doctor visits a child had that included vaccination, the higher the risk of autism. Children with one such visit had a 1.7 times higher risk of autism compared to those with none. Those with four visits—1.9 times higher. Five or more visits—2.7 times higher. And children with eleven or more such visits had a 4.4 times higher risk of autism than those without any visits.

Naturally, after the Wakefield scandal, prestigious journals refuse to publish such studies, forcing them to appear in less respected journals that serious scientists tend to do not take seriously.

Conclusion:

- All the studies that supposedly proved no link between vaccination and autism compared vaccinated children to other vaccinated children. Some of these studies actually found an association between MMR and autism but dismissed or obscured it using various methodological tricks or simply destroyed the data. All the authors of these studies had conflicts of interest.

- All the studies that directly compared vaccinated and completely unvaccinated children demonstrated a statistically significant association between vaccination and autism.