Questioning Offit. Part 4. Dravet syndrome

Previous entries:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: DTP

Part 3: Encephalopathy

At every crossway on the road that leads to the future,

each progressive spirit is opposed by a thousand men assigned to guard the past.

- Maurice Maeterlinck

To begin with, a small addition to the previous post.

In an attempt to prove that the DTP vaccine is not associated with brain damage, Offit refers to the 1991 report by the Institute of Medicine. In that report, the Institute of Medicine acknowledged that DTP can cause acute encephalopathy but was unable to determine whether DTP could lead to permanent neurological damage. However, already in 1994, the Institute of Medicine released a new report in which it concluded that there is a causal relationship between DTP and permanent neurological disorders.

Unlike the British court, which dismissed the Miller study simply by deciding that all cases of encephalopathy were unrelated to DTP, the Institute of Medicine—despite its own bias—could not afford such blatant denial of the data. It had to acknowledge the findings of the Miller study. For some reason, Offit chose to remain silent about all of this.

Dravet syndrome

After the British court finally “settled” the question of encephalopathy and epilepsy following the DTP vaccine by simply dismissing the Miller study, one question remained: what exactly causes the seizures? Twenty years would pass—and, according to Offit, everything would change. It would turn out that genes were to blame. "And the answer wouldn’t come from England, where the notion that pertussis vaccine caused brain damage had first gained international attention, or from the United States, where vaccines had almost been eliminated by lawsuits. Rather, it would come from a relatively unknown researcher on the east coast of Australia", - Offit writes.

Dravet syndrome is a form of epilepsy characterized by severe seizures that typically begin in the first year of life. It is usually accompanied by encephalopathy, developmental delays, and cognitive impairments. Dravet syndrome was first described by French neurologist Charlotte Dravet in 1978.

Offit:

In 2006, Samuel Berkovic evaluated fourteen people with severe epilepsy and mental retardation. All had developed their first seizures between two and eleven months of age; all had received the pertussis vaccine within the previous forty-eight hours; and several had been compensated for damage allegedly caused by the vaccine...

Berkovic believed that all suffered from Dravet’s Syndrome. So he looked to see whether they had a genetic defect that caused the problem. He found that eleven of the fourteen had a defect in the gene that regulates the transport of sodium in brain cells. (The specific gene is called SCN1A). Recognizing that vaccines can’t change a child’s genetic makeup—and that 100 percent of children with SCN1A defects will have seizures and mental retardation independent of whether they receive vaccines—Berkovic wrote, “The identification of a genetic cause of encephalopathy in a particular child should finally put to rest the case for vaccination being the primary cause.”

To begin with, this is not true. Not 100% of children with SCN1A gene mutations develop seizures—this claim is made by Offit, not Berkovic. Therefore, the presence of a mutation does not eliminate the question of the possible role of vaccination. Moreover, even among carriers of the same SCN1A gene mutation, symptoms can manifest differently—even leading to different diagnoses within the same family. In other words, an SCN1A mutation alone is insufficient for the development of Dravet syndrome. Consequently, environmental factors influence its onset.

That is, vaccinations, as one such factor, can indeed affect the manifestation of the disease. And, in fact, no one disputes this—the fact that vaccinations can act as a trigger for Dravet syndrome is widely acknowledged and uncontested. Even Offit admits this. The debate concerns something else: vaccination proponents argue that Dravet syndrome would have developed anyway, just later.

There are three counterarguments to this claim:

First, once again, it's not true. Unlike other genetic disorders, such as trisomy 21, which leads to Down syndrome, having a defect in the SCN1A gene does not guarantee the development of Dravet syndrome. There are individuals who live with this mutation without even knowing it, experiencing neither seizures nor intellectual disabilities.

Second, even if the disease were truly inevitable, don't additional months or years of healthy life matter? If parents had a choice regarding when their child would develop Dravet syndrome—sooner or later—wouldn't their choice be obvious? The argument that "it would have happened anyway" completely devalues the suffering of children and their parents. Moreover, preventing these cases is quite simple. Today, in most countries, all newborns undergo neonatal screening for genetic diseases (the heel prick test). Adding a check for SCN1A gene defects is neither difficult nor expensive. Such children could receive a medical exemption from vaccinations or delay vaccination until the disease has already manifested. This would give children and parents a chance for additional time without seizures—meaning a healthier and more fulfilling childhood. Yet, for some reason, no one even suggests this. No one seems to care about these children.

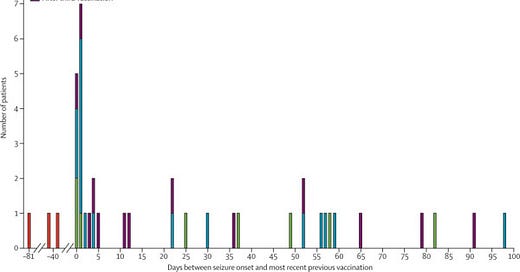

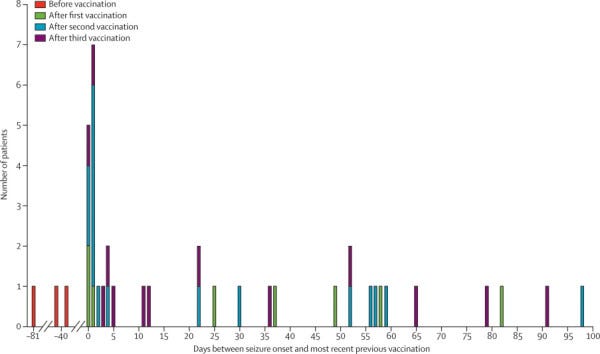

Third, even in the case of genetic diseases like Huntington's disease—which almost always develops in individuals with a specific genetic mutation—it can manifest at age 30 or at age 50. The disease may progress more mildly or more severely. Factors influencing its onset and severity include environmental factors. Vaccinations are one such environmental factor that can potentially affect the manifestation and severity of genetic diseases. Even if a disease is genetically destined to occur, there's a significant difference between developing it at 30 years old versus at 50. Here's an illustrative chart from a 2010 study by Berkovic. Out of forty cases of Dravet syndrome, only three began within 100 days before vaccination, whereas 37 began within 100 days after vaccination, with 17 occurring within five days.

Moreover, children whose Dravet syndrome began within two days after vaccination were more likely to exhibit severe intellectual disability compared to those whose disease manifested later. However, due to the small sample size, this result was not statistically significant.

This article is particularly noteworthy because it is frequently cited as evidence that vaccination does not influence cognitive development in children with Dravet syndrome. Yet, the authors actually observed a clear difference. The lack of statistical significance is most likely due to the study's limited size.

Furthermore, not only the DTP vaccine can act as a trigger for Dravet syndrome. A 2020 case report describes a 12-month-old boy who developed seizures one day after receiving the MMR, Hib, and meningococcal vaccines. He was urgently taken to the emergency department, where he suffered cardiac arrest and subsequently died. Genetic testing later revealed an SCN1A mutation. His younger sister was found to carry the same mutation. However, in her case, doctors initiated preventive treatment, including administering medications before vaccinations. As a result, she did not develop Dravet syndrome. This case clearly demonstrates that the assertion of Dravet syndrome's "inevitability" is incorrect. Even with a genetic predisposition, the disease can be prevented if identified early and appropriate measures are taken.

A 2011 case report details a Japanese girl with Dravet syndrome whose seizures began at three months of age. By age 12, she was on multiple antiepileptic medications, could speak in simple sentences, and walk, albeit with some motor impairments. She received an influenza vaccine, and three days later developed severe encephalopathy, resulting in a coma. By age 14, she had profound intellectual disability, a significant increase in severe epileptic seizures, and was left paralyzed. The authors concluded that the influenza vaccination may have triggered acute encephalopathy. This raises the question: was the vaccine truly necessary for this girl? Could it be that without the vaccination, this coincidence might have been avoided?

A 2018 French study found that in children with Dravet syndrome, vaccines containing aluminum trigger a stronger inflammatory response than in healthy children. These children produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines and fewer anti-inflammatory ones. In other words, even their immune system’s response is fundamentally different—and this very response may act as a trigger for severe complications.

A 2014 Italian study found that in children whose Dravet syndrome first manifested right after vaccination, seizures began at an earlier age and were more likely to involve prolonged, life-threatening episodes (status epilepticus). Similar results were shown in a 2015 study from Hong Kong. And a small 2022 Australian study found that children who developed status epilepticus immediately after vaccination died from it significantly more often than those in whom it developed later.

***

Before moving on from the court case that supposedly proved once and for all that epilepsy after DTP vaccination is always just a coincidence, to the discussion of Dravet syndrome, Offit states that the idea that the pertussis vaccine causes epilepsy and intellectual disability was permanently laid to rest during the legal proceedings. However, when he begins talking about Dravet syndrome, he himself admits that vaccination can serve as a trigger for its development. And yet, he fails to notice that these two positions directly contradict each other.

If the scientific community today does not dispute the fact that vaccination can trigger the onset of Dravet syndrome (even if it is not its “root cause”), then it must also not deny that vaccination could have been a trigger for Dravet syndrome in the past. The only difference is that back then, Dravet syndrome went by another name—it was called epilepsy, encephalopathy and intellectual disability.

Throughout the entire chapter, Offit cites studies, reports from medical organizations, and descriptions of legal cases, all aimed at proving that vaccination is not linked to epilepsy. But in the end, when he transitions to Dravet syndrome, he himself dismantles this framework, without even realizing that in doing so, he undermines his entire argument. Acknowledging that vaccination can be a trigger for Dravet syndrome automatically means that all those studies that failed to find a link between vaccination and seizures were, in fact, scientific fraud.

Offit ends the chapter with his interview with Samuel Berkovic:

Berkovic was surprised by the reaction to his paper. “I was very excited about this [work],” he recalled. “I thought it was one of the most, if not the most, important thing I’d ever done.” Following publication, several commentaries praised the work, one calling it the most outstanding paper of 2006. “Most of my neurologist colleagues thought that the paper was really important because they’re the people that see these cases directly. But among the vaccine community I couldn’t get any traction. We were trying to get a much bigger study together and collect more cases and we just couldn’t. I got a bit dispirited and gave up. Why didn’t it get traction? I don’t know. It befuddled me. Maybe it’s because it was something from a bygone era.”

Why Berkovic failed to gain support from the vaccine community is actually quite obvious. His small study, which was supposedly meant to shift the blame from the DTP vaccine onto genetic factors, in fact proves that all those studies that, for decades, repeatedly claimed there was no link between vaccination and epilepsy—were actually wrong. And that the real truth lay in the many case series published since the 1930s, which were later dismissed as mere coincidences. The true findings were those of Miller and Baraff—studies that, as Offit writes, were “completely dismantled” by later research and court rulings.

Those working in the field of vaccination fully understand that Berkovic’s study portrays them as scientific fraudsters. That’s precisely why he was never able to gain their support.

*****

Chapter Three contains 54 footnotes, which include 28 footnotes with studies.

The studies cited tell us that:

– The vaccine contains foreign proteins (1 footnote)

– The majority of patients with post-vaccination encephalopathy have a genetic defect (3)

– Vaccines are not safe (5)

– Studies unrelated to vaccination (4)

- 15 footnotes are presented as evidence of vaccine effectiveness or safety and were discussed in this and previous entries.